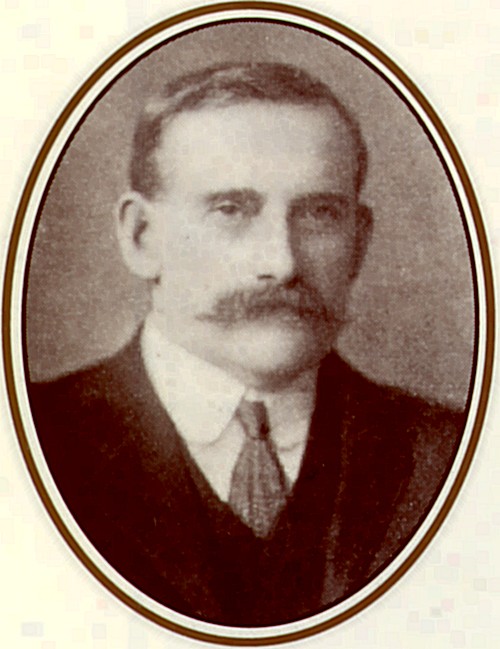

Joseph Bell and

the 'Titanic'

Joseph Bell and the 'Titanic' Disaster

|

|

||

| This

page records significant events and writing

recounting the inspiring and heroic story of

Joseph Bell, Chief Engineer of the 'Titanic', a

member of St Faith's congregation who is

commemorated in the much-visited memorial plaque

in the south aisle of our church. The most recent

additions appear immediately below. |

September

3rd, 2016 September

3rd, 2016Titanic Sinking-Engine Room Heroes, by castlehead UNSUNG HEROES OF THE ENGINE ROOM Chief Bell's Men Kept Titanic's Lights Burning Until She Went Down. KNEW HER WOUND WAS FATAL Yet All Stuck to Their Posts and Perished to the Last Man---Builders' Engineers with Them. "The lights were burning all over the ship until shortly before she went down." This is the testimony of the survivors of the Titanic. It was her engineers who kept the lights burning, and in the list of heroes who went down with the vessel the names of the men of the engineering force will have a high place. Not one of them was saved, although many of them were off duty, and these had some chance of climbing to the deck. While it will never be known just what happened, it is believed that every one went back to his post instead of to the decks. Engineers stand small chance for life in a sea disaster, and they know it. It is a tradition that when the engineers on a sinking vessel have done their duty to the last they gather in the engine room, clasping hands while standing about the engines, and so go down with their vessel. The Titanic's engineers have been overlooked in the bestowal of praise. Besides the engineers of the regular ship's force there were on board twenty guarantee engineers, representing the builders and holders of engineering contracts, and so called because they make the first few trips on a new vessel to see that the machinery comes up to the guarantee. All these were the first to know the desperate nature of the damage to the Titanic. They must have worked at high tension, for they were the first to note that rising of the water, the uselessness of the pumps, and the impossibility of keeping afloat. They had little time for thought, however, for they had to keep the dynamos going, the pumps working, look after the bulkhead doors, and keep the stoke hole force at work. Most of them probably died at that last explosion which tore the Titanic asunder as she went down. The men were assigned each to his own task. There are hydraulic, electrical, pumps, and steam packing men, and besides the regulars the guarantee men were there to lend a hand. It was not a duty call that kept the guarantee men below, for they were in no sense part of the crew. The duty of the guarantee engineers is to watch the working of the great engines, see that they are tuned up and in working order. They also watch the workings of each part of the machinery, which has nothing to do with the electrical light dynamos and the refrigerating plant. The conduct of one man stands out conspicuously, according to the stories told by members of the crew. Archie Frost, builder's chief engineer, representing Harland & Wolff, was not in the engine room when the crash came, but he climbed down the steep iron ladders to the engines and death. When last seen he was there. With him was Thomas Andrews, designer of the Titanic. When the collision came there was no call of duty to keep him from the deck and the only chance of escape, but he would not take that chance. The last time Andrews was seen by any one alive was in the engine room with Frost and Bell, the Titanic's Chief, and all were working too hard, perhaps, to think much of the slowly gaining waters. Every man in the White Star Line is to-day mourning the loss of bluff, genial Joseph Bell, Chief Engineer of the Titanic and Senior Engineer of the line. Bell was about 50 years old, and he had spent thirty-six years in the service of the company. He was married, and lived in Liverpool. Some of his children are now attending school in Glasgow. It is said of him that he was the best marine engineer in Great Britain, and knew more about steam vessels than any other man in his profession. Under him were two second engineers, three third, and twelve junior engineers. Second Senior Engineer Farquarson had been with the company fourteen years, and Second Engineer Harrison had served sixteen years. Although a young man. Intermediate Second Engineer Harry Hesketh had seen nineteen years of service. He began the practice of his profession with the White Star Line, and had never served in any other. The junior engineers, "the kids" they called them on shipboard, each one a mere lad, proved themselves men indeed, for they stuck to their work and went down with the ship. Engineers Rarely Saved."The engineers were not deceived by false hope. They were in a position to know how badly the vessel was injured. Then they worked in an uncertainty which must have been maddening. On deck the crew and passengers could see what was going on. Down in the engine room they could not tell how the work of lowering the boats was progressing. They had no chance and they must have known it. They did not hear the Captain's last word as the vessel began to sink that duty done, every man must take care of himself. Even if they had they would never have been able to climb up steep iron ladders before they could reach the deck. It was ninety feet from the water line to the boat deck, and they were thirty-two feet below that. "They died like men," said Mr. Hunter, (Secretary of the American Seamen's Friend Society) "and their bravery seems to have been overlooked. It can be said of them that, like the higher officers, they stuck to their posts until death." Report from The New York Times 23 April 1912. |

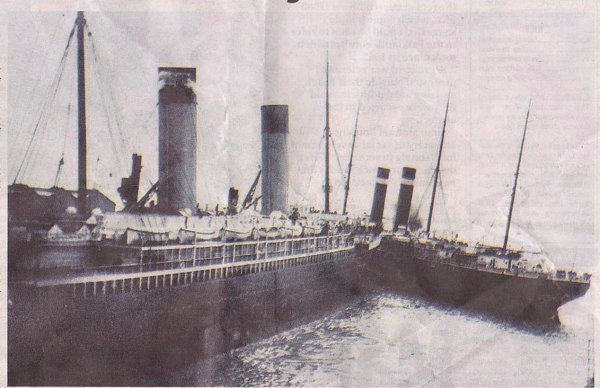

| October 8th, 2014 In an article in the Liverpool Daily Post, October 4th, 2014, Daily Post Correspondent Rod Minchin writes of an apparent narrow escape from collision on the Titanic's maiden voyage. The incident is described by Joseph Bell in a letter to his son, and is accompanied by an unattributed photograph described as being 'the near-miss depicted by chief engineer Joseph Bell'  Titanic Near-Miss Letter describing liner’s close shave is to go under the hammer It was the worst of omens for the gleaming new ship embarking on its maiden voyage. As the Titanic left Southampton docks for a journey that has gone down in history, the ship came close to hitting two other liners. Had they collided, it would have cut short the Titanic’s ill-fated voyage to New York and may well have averted the catastrophe that was to claim 1,500 lives when the boat6 struck an iceberg on April 14 2014. The near miss is described in a letter from the Titanic’s chief engineer Joseph Bell to his son Frank, which is to go under the hammer later this month in Devizes, Wiltshire. Mr Bell told his son, who was training in Belfast to be a ship’s engineer like his father, how the mooring ropes of the New York and Oceanic liners broke as the Titanic passed, causing the New York to set off across the river. ‘We nearly had a collision with the New York & Oceanic when leaving Southampton, the wash of our propellers made the two ships range about when we were passing them, this made their mooring ropes break and the New York set off across the river until the tugs got hold of her again, no damage was done but it looked like trouble at the time, keep well and be a good lad, regards to Mrs Johnston.’ Mr Bell died in the disaster. |

| April 15th, 2012:

Remembering Joseph Bell On the 100th anniversary of the sinking of the 'Titanic', an Act of Remembrance took place at the end of the morning service at St Faith's. It included the first performance of an anthem, 'They that go down to the sea in ships', by our organist, Daniel Rathbone. Commemoration to mark the Anniversary of the Sinking of the Titanic The Lord is my Pilot: I shall not drift. He lighteth me across the dark water, He steereth me in the dark channels, He keepeth my log, He guideth me by the Star of Holiness for his name’s sake; Yea, though I sail amid the thunder and tempests of life, I shall dread no danger, for thou art with me; Thy love and thy care, they shelter me, Though preparest a harbour before me In the homeland of Eternity: Thou hast anointed the waves with oil, My ship rideth calmly, Surely sunlight and starlight shall favour me In the voyage I take, And I will rest in the Port of my God forever. Anthem: They that go down to the sea in ships – Daniel Rathbone Act of Commemoration (stand) Let us remember before God and commend to his sure keeping those whose lives were lost in the Titanic disaster, those whose courage and bravery helped to save the lives of others and all who have lived and died to bring peace and hope to others. Especially we remember Joseph Bell, Chief Engineer on the Titanic and a member of this church, whose heroism is commemorated here and for whose example of courage and devotion we give thanks to God. Two minutes’ silence follows. Lord God, creator of all, you have made us creatures of this earth but have also promised us a share in life eternal: receive our thanks and praise this day As we recall those whose lives were lost with the sinking of the Titanic. Through the passion and death of Christ, may your children whom we commemorate today, share with your saints in the joy of heaven, where there is neither sorrow nor pain but life everlasting. Amen. Alleluia. Rest eternal grant unto them, O Lord And let light perpetual shine upon them. May they rest in peace And rise in glory. Alleluia! |

In Memoriam: Joseph Bell 2012 marks the centenary of the sinking of the Titanic. Dr Denis Griffiths' article below was originally printed in the booklet 'Furnishings of Faith', an anthology of articles about the architecture, furnishings and memorials in our church, and describes the heroism of the Chief Engineer of that famous ship, who lived locally and was a worshipper here. In this centenary year, we have marked the event with an Act of Remembrance during the course of our Sung Eucharist on Sunday, April 15th, at which there was the first performance of an anthem, entitled 'They that go down to the sea in ships', by our Director of Music, Daniel Rathbone: see the panel above for the order of service on that day, then read Denis' stirring narrative below. |

On the wall in the south aisle of St Faith’s there is a brass tablet commemorating the life, and death, of Joseph Bell. The ‘Titanic’ is probably the most famous ship which ever sailed the seas, and there are many monuments commemorating her sinking and those who lost their lives in that most tragic disaster. Numerous books have been written about the ship, but none makes mention of the memorial to be found in St Faith’s, and that alone makes the brass tablet something special.

Joseph Bell was born in May 1861 in Farlam, near Brampton, Cumberland, and received his education in Carlisle before serving an engineering apprenticeship with Robert Stephen & Co. of Newcastle-on-Tyne. He commenced his seagoing career with the Lamport and Holt Line in 1883 and joined the White Star Line two years later. Following service aboard many ships on the fleet, both on the New Zealand run and the New York service, he was appointed Chief Engineer of the ‘Coptic’ when only 30 years old. After a short spell as Chief Engineer aboard the ‘Olympic’, sister ship of the ‘Titanic’, he was transferred to the latter whilst she was being completed by Harland and Wolff in Belfast. For the delivery voyage from Belfast to Southampton he was accompanied by his eldest son, who had just begun an apprenticeship with Harland and Wolff.

The story of that first and final voyage of the ‘Titanic’ is too well known to be repeated in detail here, but following the collision with the iceberg at 11.40 pm the ship sank less than two hours later. With her she took the lives of some 815 passengers and 688 crew, including Joseph Bell and all of his engineering officers. Only 703 people were saved.

The library of books written about the disaster detail the events on deck during that eventful night, but little mention is made of the engineers who kept the ship afloat for so long in the vain hope that rescue might come. As no engineers survived, there was nobody to realise what they did, but it is possible to piece together the events below from White Star standing instructions and marine engineering knowledge. As soon as the message from the bridge came for engines to be stopped, and the nature of the incident was known, all engineers would have been summoned by means of alarm bells. Joseph Bell would then have directed them to various tasks as required.

Collision with the iceberg caused sea water to enter six watertight compartments including No 6 and No 5 boiler rooms. Watertight doors were immediately closed, thus preventing water from flooding all machinery compartments, and the pumps were started in order to try to keep the water in check. Bell would have quickly seen that the task was hopeless and that the ship would sink; it was just a matter of time. Time, however, was what he could give by keeping pumps working and preventing bulkheads from collapsing. ‘Titanic’ had been designed to keep afloat with up to three watertight compartments open to the sea, but she could not survive with six compartments flooded.

The transverse watertight bulkheads only extended a certain distance above the normal waterline and as the ship sank lower in the water, the water flooding those compartments would flow over the tops of the bulkheads into the adjacent compartments. The ship was doomed: Joseph Bell knew it and so did his engineers, but they all stayed at their allotted tasks until the end. Those tasks including stopping as many leaks as they could, shoring up bulkheads and keeping the pumps, dynamos and a few boilers working to supply the limited amount of steam now required. Other boilers had to be shut down, steam being vented and fires removed from grates. This was essential as there was a risk of these boilers exploding if normal feed water supply was not maintained, and during the emergency that could not be guaranteed. The dynamos kept the lights going as the ship sank deeper and ensured that those entering the lifeboats could do so with less danger than would have been the case in the inky blackness of a north Atlantic night.

When the order came to abandon ship the engineers stood no chance of escape as they were deep in the heart of the ‘Titanic’. It is unlikely they all drowned: many would have been crushed by boilers and machinery breaking away from mountings as the ship’s bow sank deeper in the water; others would have been scalded by high-temperature steam released as pipes became detached when boilers broke free. They all died doing their duty.

Joseph Bell was 51 years old; he left a widow, Maud, and four children: two boys and two girls. Ralph Douglas Bell, the youngest child, had been baptised at St Faith’s on 29 March 1908. The family lived at 1, Belvidere Road, Crosby and had regularly attended the church since its construction. At a packed special service held at 8.00 pm on 6 January 1913 the memorial tablet was unveiled by the Bishop of Liverpool. The collection taken at the service amounted to £6 2s 0d (£6.10 in 'new' money) and was donated to the Seamens' Orphanage.

According to the ‘Crosby Herald’ for that week, the Bishop gave a moving and eloquent address, choosing as his text Revelation 11 v, 10: ‘Be thou faithful unto death, and I will give thee a crown of life’. Joseph Bell and his engineers were indeed faithful unto death: they sacrificed their lives that others might have a chance of living, and they undoubtedly deserved their crowns.